In 1998, I settled into my stylist’s chair holding a photo of Gwyneth Paltrow sporting the pixie cut she made famous in the movie Sliding Doors. You might recall the film; in it, Paltrow’s character experiences two different life paths. In one scenario, she catches the subway just as the doors slam shut; in the other, she doesn’t make it. In the version where she succeeds, she gets home sooner than her boyfriend anticipated, only to discover him in bed with another woman. She ditches him, chops her hair, and embarks on a new journey. Conversely, in the other scenario, she arrives home as expected, retains her long locks, and holds onto her delusions.

Initially, my stylist attempted a mini-intervention. She informed me that although she could give me that haircut, it wouldn’t replicate Gwyneth Paltrow’s look due to my different hair type. I proceeded anyway. She was correct.

Every time I get a haircut, then and now, a part of me expects that a new version of me will emerge. However, come the next day, I realize it’s merely me… with a different haircut. It’s a tough lesson: transformation and growth are possible, but you remain fundamentally you. With highlights. A new profession. A daring lip color.

Last year, I ended a four-year relationship with a man, a police officer in NYC. It was the longest relationship I’d ever experienced. And that was sufficient. I had spent 25 years living independently, carefully guarding my time and freedom. So I was upfront with him from the start: I had never cohabitated with a man and had no plans to do so now. However, he held beliefs as well about love’s transformative power, and that a gradual merging of lives was a natural course of events. The reality was, I remained myself… with a boyfriend. I chose to end it, perhaps later than I should have.

They say you can’t simply switch a light and decide to be gay. And to be fair, that’s not exactly what occurred: I’d harbored strong feelings for various women throughout my life — kissed my college best friend, developed a crush on a folk musician in my twenties, even had encounters with a few bored, bisexual wives in my thirties — yet I regarded them as sporadic, frantic exceptions.

After all, I had only dated men and never really questioned that reality. Nobody else did either. This is how self-identity can solidify: no evidence to suggest otherwise. Even the women I found attractive for reasons I couldn’t describe seemed to confirm my heterosexuality: I was so straight that I was even drawn to women who resembled men.

Yeah, that’s not quite what that indicates.

A month after my breakup, and interestingly, a week after I officiated my friends’ same-sex wedding — coincidence? — I switched my dating search to women. Just to explore.

The majority of the profiles didn’t catch my interest. Then I encountered her: a woman with a bleached pixie cut, a streak of blue hair cascading over her eyes. She resembled less a woman and more a nymph, a fairy who would enchant you in a golden forest and keep you captivated in the hollow of an ancient elm for centuries.

We matched. I warned her upfront that I was the last person she should want to meet. Firstly, I wasn’t gay — and worse, I had just come out of a long-term relationship.

“If I were one of your friends,” I wrote, “I’d advise you to run.”

Nonetheless, we met for coffee. A week later, we did brunch. I felt like I was auditioning for a role I wasn’t ready for. We shared a shy kiss at the intersection of 72nd and Broadway, and I quivered the entire journey home.

“Do you like her?” my friend inquired. “I mean, do you want to date her or just go shopping with her?”

I was unsure. A part of me thought there was no lesbian on the planet who could take me seriously. How could they? With so many years of dating men behind me?

The blue fairy texted me the following day, saying I had been on her mind. “I was thinking about your hair,” she mentioned. “I love it.”

“Why don’t I come over tonight?” she suggested.

“Sure,” I answered. “Should I prepare dinner?”

“Let’s forgo dinner,” she replied.

SOS, I messaged my friends: “She’s coming over shortly, and we’re not having dinner. All caps. THERE IS NO DINNER.”

“You’ll be fine!” they reassured me. “Enjoy!”

She showed up at 6 p.m. I had to come down from cloud nine to open the door. I know you don’t drink, I said, but I’m going to need one.

I shook a dirty martini with vigor in the kitchen and then perched beside her on the couch. It felt like straddling a fence, preparing to leap.

And then she kissed me. I’ll avoid over-exaggerating when I say that it felt as though I had just resurfaced from countless leagues beneath the ocean. As if I’d never inhaled before, and would never have enough air.

The following day was April 8th, which I remember because it was the solar eclipse. Although Manhattan wasn’t in the path of totality, the light dimmed as if controlled by a dimmer switch, and the colors faded to sepia tones. My friend Kim and I were perched on a wall in the park, taking turns peeking at the sun through flimsy glasses as it dwindled to a bright crescent.

“So, this is occurring,” she stated. “Right?”

It seemed a significant understatement to simply say yes. Indeed, yes. I had never felt more yes.

Moments later, the sun brightened fully, the colors returned, but everything appeared altered.

When I say I “came out,” it’s not that I had been concealing a secret. More so, I’d stumbled onto something astonishing, like finding a unicorn in my kitchen. How did that end up there? What am I to do with it? And then wanting to share this revelation with every person I’d ever known.

I can’t speak for all later-life lesbians, but I believe my experience was relatively smooth. When I confessed to my friends that I was now dating women, it felt akin to showing up at brunch with bangs. They reacted, Whoa, wasn’t expecting that; what matters is that you’re happy with them.

People were quick to give me an out — stating things like, “You may not be gay; you could just be in love with this person.” Yet I didn’t need protection from it. Being gay felt correct. It’s akin to saying, perhaps you simply enjoy this omelette; it may not signify anything more.

No, I’m quite certain I relish eggs. Period.

I fell utterly for this blue fairy, to the astonishment of myself and others. Me, who had historically taken her time before embracing the girlfriend role and resisted relinquishing my single status. Yes, I desired to be her girlfriend. Right now. When she suggested potentially moving from her apartment ten blocks away to Brooklyn, I was inconsolable.

With my girlfriend, I behaved differently than I had with any man: tenderness and flexibility, treating her like fragile glass. I told her she was the sole one for me, and I genuinely believed it.

Perhaps this was my dilemma! I wasn’t detached and commitment-averse — perhaps I was simply gay. And now that I accepted my true self, surely this would rectify everything.

Yet deep inside, that part of me that always worried I wasn’t intelligent enough, good enough, or attractive enough simply developed a new concern: That I wasn’t gay enough. That I was only gay because of her, that I was just… gay through association.

It didn’t take longer than a month or two for red flags to appear and for the blue fairy to show her true colors as a master manipulator. By July, tensions escalated: She accused me of having the “wrong attachment style”; I countered with claims that she demanded more than anyone could provide. We were likely both correct.

You probably know where this is heading. It ended just as swiftly and tumultuously as it had begun. It was the most gut-wrenching breakup I’ve ever experienced.

My entire life, my fear of commitment had been rooted in the belief that I would vanish into a relationship with a man and cease to exist. What plagued me now was the thought that if I let her go, this gay iteration of me would depart along with her.

It took time to realize that I could and would still identify as gay without this individual. What I was truly mourning was the loss of something I could never actually lose: myself.

I didn’t require a girlfriend to be gay, nor did I have to change. In essence, I was still just me… with a new sexual orientation.

A year later, I’m pleased to share that I’m still here. I remain gay. Same hairstyle; new dawn.

Terri (right) with her sisters.

Terri Trespicio is the author of Unfollow Your Passion: How to Create a Life that Matters to You. Her TEDx talk, “Stop Searching for Your Passion,” has garnered over eight million views. She received her MFA in creative writing from Emerson College and resides in Manhattan. She is also the founder of The New Rules Studio, a live writing workshop to help you complete your projects.

P.S. “What nine films and shows with gay characters signified to me,” and the “little gay house” in Portland, Oregon.

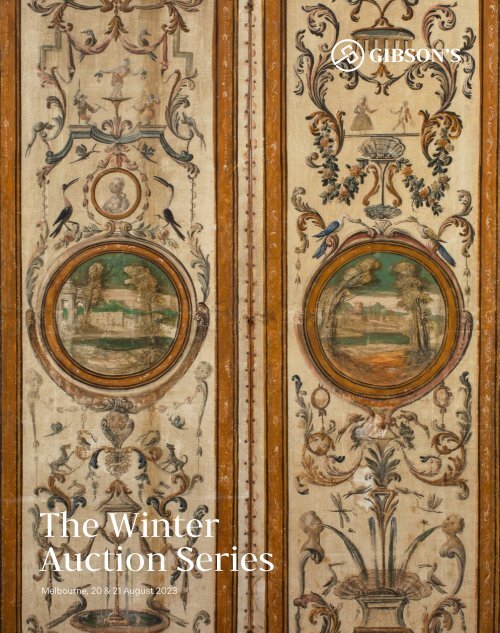

(Illustration by Julia Rothman for Cup of Jo.)

**The Similarities and Differences Between Coming Out and Getting a Haircut**

Coming out and getting a haircut may initially seem like disparate experiences. However, both involve expressions of self and can greatly impact an individual’s life. This article examines the similarities and distinctions between these two experiences.

**Similarities:**

1. **Personal Expression:**

Both coming out and getting a haircut serve as forms of personal expression. Coming out is a declaration of one’s sexual orientation or gender identity, while a haircut can showcase personal style and individuality.

2. **Emotional Impact:**

Both experiences can evoke strong emotions. Coming out often entails vulnerability and fear of rejection, whereas a haircut might bring anxiety over change or excitement about a new appearance.

3. **Social Reactions:**

Each can provoke responses from others. Coming out can lead to acceptance or discrimination, while a new haircut can draw compliments or critiques.

4. **Empowerment:**

Both can inspire empowerment. Coming out can lead to a sense of authenticity and liberation, while a haircut can enhance confidence and self-esteem.

5. **Decision-Making:**

Both necessitate decision-making. Coming out involves choosing when and how to reveal one’s identity, while selecting a haircut entails decisions about style and length.

**Differences:**

1. **Permanence:**

Coming out is a significant, often lifelong commitment, while a haircut is temporary and can be altered or grown out.

2. **Societal Impact:**

Coming out can have broader societal consequences, challenging norms and fostering social progress. A haircut is usually viewed as a personal decision with limited societal influence.

3. **Frequency:**

Coming out is typically a singular or rare occurrence, while haircuts are routine and can be regularly acquired throughout a person’s life.

4. **Risk Level:**

Coming out can entail considerable personal risk, including the threat of discrimination or estrangement from loved ones. A haircut, while potentially risky in terms of personal satisfaction, usually poses less social risk.

5. **Cultural Significance:**

The cultural relevance of coming out is profound, usually related to identity politics and human rights. Haircuts, while culturally meaningful, do not carry the same gravity regarding identity politics.

In conclusion, while coming out and getting a haircut share similarities in personal expression and emotional significance, they markedly differ in terms of permanence, societal implications, frequency, risk level, and cultural significance. Both experiences, nonetheless, play crucial roles in individual identity and self-expression.